Picking Newell’s Parautoptic Lock – The Second Great Lock Controversy?

Written in collaboration with Lynn Collins. First published in the WCLCA Publication

What follows is the narrative of the picking of Newell’s Parautoptic Lock. It is rooted in history with a mixture of facts and inferences and weaves the tale of three great lockmakers, Newell, Yale Jr., and Hobbs. While this article does not intend to be a comprehensive evaluation of these lockmakers’ biographies and of the mechanics of Newell’s lock, it does strive to tell the story of a pivotal moment in bank lock history.

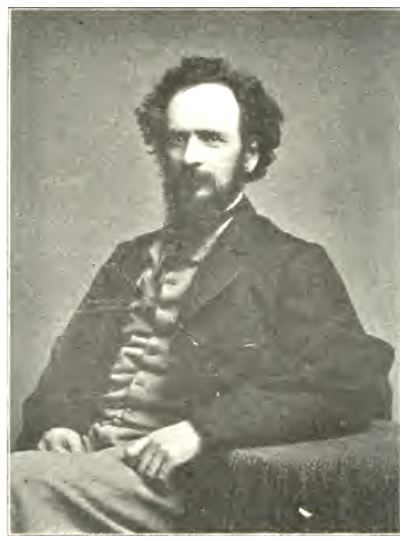

We’ll begin with a brief introduction to Robert Newell and his invention, the Parautoptic Lock. Robert Newell was a man of great strength and character, drive and ambition. He was resolute in his decisions and possessed a great deal of confidence in his choices. Although great in mind and body, his tactic was one of physical force and domineering leadership. He was skilled in convincing people to believe in him and his team’s work.(1) Employed by him was a key salesman, Alfred Charles Hobbs, who helped by adding charisma and personal charm. An introduction to Hobbs will follow later in the story.

Newell formed a partnership with Mr. Day in 1833 to begin the Day and Newell firm(1), specializing in secure bank locks. Newell went through several iterations of locks, all suffering from either his own admission of pickability or as a result of challenge. In 1838, Newell invented a changeable bit key lock, much like Solomon Andrews’ similar creation, that was capable of accepting various configurations of the same key (Patent 944). The lock featured two sets of tumblers on which a key with changeable bits acted. However, within a few years Newell demonstrated that both Solomon Andrews’ lock and his own were both pickable, revealing the method to the public in an effort to prevent embarrassment at the hands of another.(2) Newell then improved his lock in 1843 (Patent 3135). This improved lock featured a similar design but with the addition of notches on the bordering ends of the first and second tumblers. If pressure were applied to the bolt while picking the lock, the tumblers would bind on the false notches and prevent picking. Newell’s improved changeable bit key lock invention was soon defeated by Mr. Pettit, an American machinist costing his company 500 dollars and their reputation.(2)

Needing a solution to this problem, Newell went back to the drawing board, and in 1844 patented his famous Parautoptic Lock. The name being devised from the Greek for “concealed from view.”(3) (Patent 3747. Later improved in 1851, Patent 8145. Additionally, patented in Great Britain dated April 15, 1851, Patent GB13595). This lock added a third intermediate tumbler to the construction, leaving only the first tumbler accessible from the keyhole. This effectively eliminates the ability to pick the lock utilizing pressure on the tumblers as the tumblers acting on the bolt are hidden from view. An attempt at preventing traditional methods of smoking the lock is also accomplished through the use of a rotating tumbler on the outside of the lock that revolves around the keyhole whenever the key is turned into contact with the first tumbler. There is more to the lock’s complex construction than that, but the exact details of the locks evolution and construction are best kept to another article. One more item of note though, this lock added another important feature. The lock could now be re-keyed simply by changing the order of the bits of the key with no need to change any internal components.(2)

This lock went on to achieve great fame and fortune for Newell, being installed in hundreds of locations. Newell even wrote a book called Important to Bankers. Bank Robberies Prevented by Newell’s Patent Parautoptic Bank Lock in 1850. Newell raves about the many awards, accolades, tests, and references his lock has achieved. Newell’s head salesman for the lock was a guy by the name of Alfred Charles Hobbs. Hobbs had a widely varied career before he went to work for Day and Newell. He studied woodcarving before the age of 16 when he then went to work cutting glass for the Sandwich Glass Company. After 8 years, he then opened his own glass cutting business before tiring of this and going to work as a salesman for Edwards & Holman, a safe and lock manufacturer, where he gained knowledge of the inner workings and construction of locks. He then jumped ship to work for Day & Newell, and this is where our story continues.(4)

Hobbs traveled all through the United States, from New Orleans to New York, picking existing bank locks and selling Newell’s as a more secure replacement.(5) After proving its success in the United States and cementing his lock-picking skills, Hobbs took Newell’s lock to the 1851 International Exhibition in London where he displayed a specially made 15 lever lock.

Hobbs spent his time in London exhibiting his superb lock picking skills and caused the Great Lock Controversy, a topic on which pages could be written. In short, however, Hobbs succeeded in picking two of the great English locks manufactured by Chubbs and Bramah which were in use in the majority of secure installations throughout England. This gave him instant fame. It would only be fair if Hobbs allowed challenges against his Newell lock, and so he did. A telling of one such challenge by a Mr. Garbutt is found in Construction of Locks and Safes. After 30 days, and with access to the internals of a similar lock, Mr. Garbutt was unsuccessful in picking Newell’s lock. These actions garnered a reputation for Newell’s locks throughout England. Newell’s business and reputation boomed, with seemingly no ceiling in sight. After Hobbs’ successes in London, he created a lock manufacturing factory there, initially distributing Newell’s lock.

Though it soon all came crashing down for Newell. Day & Newell’s booming business took a blow in 1855 that would eventually be the end for them when Linus Yale Jr. challenged Newell’s lock. Yale Jr. (born April 4, 1821) is a man who needs little introduction, so it will presently be kept very brief. Yale Jr. is the son of Linus Yale Sr., inventor of the Yale Quadruplex lock which is thought by many to be the first commercialized modern pin-tumbler lock. Yale Jr. joined his father’s lock business around 1849 and soon became a consultant for other lock and safe manufacturers of the day.(7) Throughout his travels, he would have experienced all sorts of locks and people, and in 1855 he accepted Newell’s challenge to pick the famous Parautoptic Bank Lock.

How did Yale Jr. pick this “unpickable” lock? It is the intent of the remainder of this article to detail the possible mechanism for picking this lock and hypothesize that another famous lock-picker of the time might have had some influence.

Yale Jr’s method was very ingenious, defeating the lock with only the simplest of materials. In the lock-picking challenge, the banker would likely unlock the lock using his key as proof the lock worked. While distracted and with the lock unlocked, Yale could simply insert a stick or other device coated in some sort of black marking material, such as grease or printing ink, through the keyhole thus coating the tumblers with the marking material. The owner would then turn his key to re-lock the lock in preparation for the lock-picking attempt, leaving an impression on the tumblers. All would appear fair and square to those observing with just a little misdirection on Yale’s part. At this point, the stage is set, and it is up to Yale to display his magic (coincidentally, the name of one of his famous lock inventions). The markings on the tumblers would need to be read. A small mirror or reflective object could be utilized to determine the length of each bit. While this might have been an earlier way the lock was picked in developing the final method, a much simpler approach exists. Instead of a mirror, a “pine stick”(7) cut to the proper shape and size of a legitimate Newell key could then be turned in the lock, retrieving the markings thusly made on the tumblers. With the correct bit lengths known, the wooden key could be carved down to the mimic the correct bits and turned to unlock the lock. Making this even simpler, the same wooden key carved to unlock the lock could have even been the device used for marking the tumblers by simply applying the marking material on the flat exterior of the wooden bit.

Linus Yale Jr.’s own Dissertation on Locks and Lockpicking and the Principles of Burglarproofing published in 1856 corroborates this method, stating that “his method is so exceedingly simple that any smart lad of sixteen can in short time make a wooden key…which will open these locks…in an incredibly short space of time.” As a side note, the Dissertation even presents an interesting point. Once the lock has been unlocked using the wooden key, another key cut to any other combination could then be used to re-lock the vault leaving the owners with no recourse but to break open the vault with force instead. The Dissertation continues to provide letters from bank representatives who witnessed his picking prowess. The lock has been defeated, Day and Newell’s reputation destroyed, and Yale Jr. now has a leading opportunity in America to take over Day and Newell’s customers. The tale could end here, a fitting end for sure to this great tale of Newell’s rise to prominence and Yale’s crushing blow. But, was Yale Jr. the first to discover how to pick this lock? Or, was it first discovered by Hobbs who allowed Yale Jr. to utilize his method?

Although merely conjecture, the facts do help lend some credence to this theory. Hobbs was well known for lock picking and had considerable time and exposure to Newell’s locks. As a salesman, he also witnessed failed attempts against said locks. Being the best in his field of lockpicking, he would have desired to hone his skills by picking the previously “unpickable” lock. Hobbs also had experience in glassworks and woodcarving, both possibly methods utilized to study and eventually pick Newell’s lock. Yale and Hobbs would have crossed paths at some point, both traveling the countries in the same line of work. Hobbs had his business in Great Britain; Yale had his in the United States. It is not impossible to fathom that a monetary agreement could have been reached, on which Yale would expose Newell’s locks, and in exchange Yale would not pursue the British markets where Hobbs had his business.

At first glance, it would seem there is one critical flaw in this thought. Wouldn’t this agreement hurt Hobbs’ business? He was, after all, selling Newell’s locks. Well, in 1855, just prior to Yale’s defeat, Hobbs partnered with Mr. Ashely, likely providing a financial influx to the business. Additionally, Hobbs’ had his other locks, such as the Hobbs’ Protector, lock to help support his business as well. If he could withstand the hit from the damaged reputation of Newell’s locks, perhaps he could take over all of Newell’s business in Great Britain and go from minor dealer to leading manufacturer. In fact, it does appear his business took a hit after Yale Jr. picked Newell’s lock(4), but he resumed production of Newell’s lock with one key improvement.

This improvement was a simple wiper system that would wipe the tumblers down after the key was turned, removing any potential marking material from them and rendering Yale Jr.’s method obsolete. In another interesting twist, Yale patented this improvement in the United States in June 1856 (Patent 15031). This patent effectively prevented Newell from fixing their locks, but no record can be found of Yale pursuing action against Hobbs for using this improvement in Great Britain. It is believed that this was part of the agreement and a creative means of enforcing it. Yale owned the patent in the United States so Hobbs couldn’t sell his improved lock there without infringing, and Yale didn’t patent it in Great Britain thus allowing Hobbs to continue production. According to the The Encyclopædia Britannica published in 1857, Hobbs was already making the locks with the improved “revolving curtain” to wipe the marking off.(8) Hobbs further improved the lock adding his patented anti-pressure device (Patent GB13985). The agreement would prove beneficial to both companies, with the Yale lockmaking company becoming one of the most successful in the United States and the Hobbs company going through a series of acquisitions as one of the more successful operations in Great Britain. Both former companies continue to operate to this day, albeit under different names.

Perhaps, the Great Lock Controversy of 1851 wasn’t the only great controversy involving Hobbs.

References:

1 The American Phrenological Journal and Repository of Science, Literature and General Intelligence: Volumes 13-14. January 1, 1851. Pages 98-100

2 The Engineer and the Machinist: A Journal of Mechanical and Manipulative Art: No. 1. March 1850. Pages 188-189

3 Locks and Safes. The construction of locks. A. C. Hobbs. 1868. Page 88

4 Transactions of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Volume XIII. 1892. Pages 263-274

5 Important to Bankers. Bank Robberies Prevented by Newell’s Patent Parautoptic Bank Lock. Day & Newell Properties. 1850

6 London News: Vol 19. July to Dec. 1851

7 Yale Genealogy and History of Wales. 1908

8 Dissertation on Locks and Lockpicking and the Principles of Burglarproofing. Linus Yale Jr. 1856

9 The Encyclopædia Britannica, or Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature: Eighth Edition. Adam and Charles Black. 1857. Pages 543-545